Übergordnete Werke und Veranstaltungen

Filmprogramm

Looking at the Animal

Personen

Media

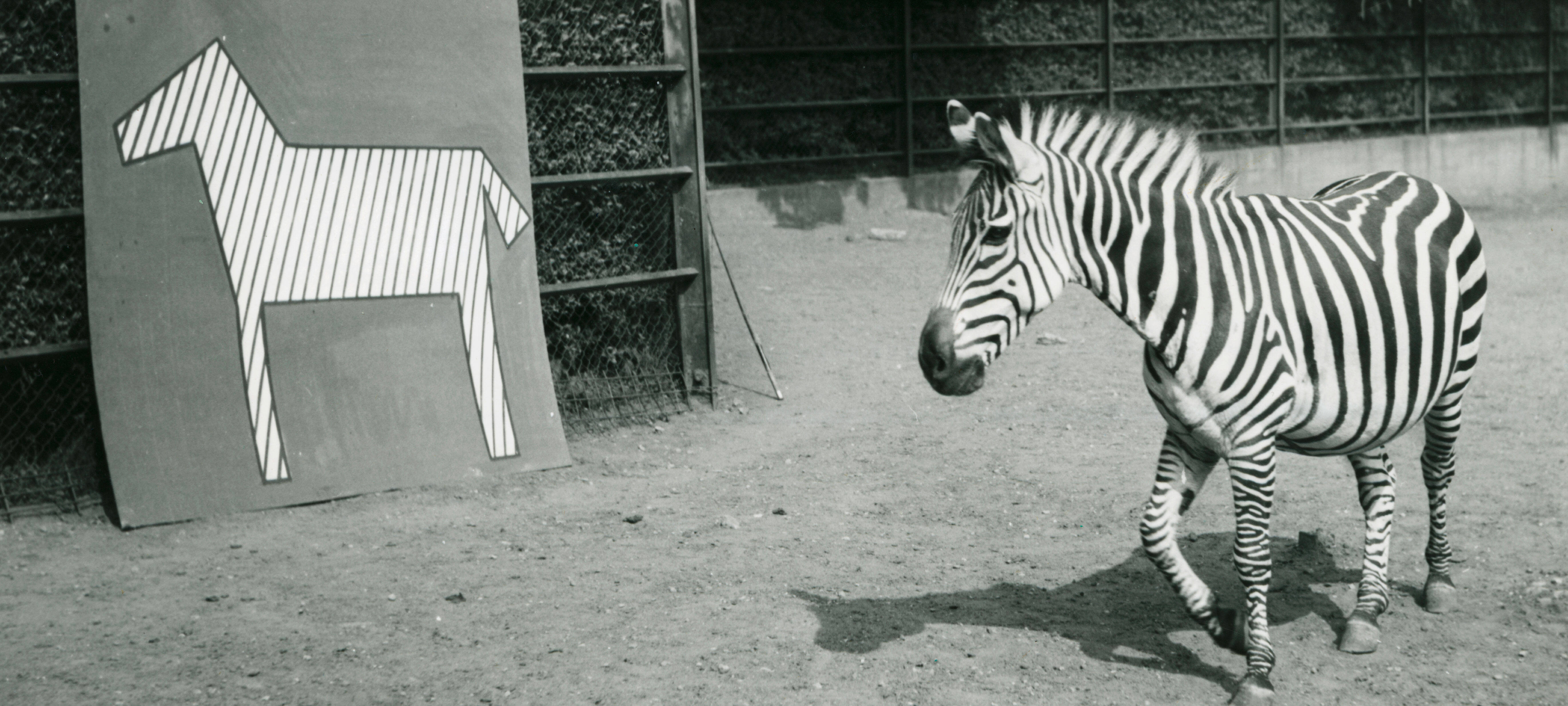

Are we capable of just looking at animals or has the age of "Okulartyrannis", as the philosopher Ulrich Sonnemann titled the image-addicted modern period, rendered our gaze permanently instrumental?

At least it is possible to try to 'just' film an animal with the camera. The images in the film Naturschutz: Tieraufnahmen I (Nature Conservation: Animal Shots I), made between 1915 and 1920, do this. They show different animals, mostly birds, in their natural environment without commentary. The title, however, makes the images disturbing. Evidently it's necessary to show people the animals in order to make them understand that they are under threat. Prior to the images they had vanished from daily consciousness. With some types of fish the case is different. Aquarium fish are among the most popular ornamental animals. Gazing at an aquarium is a sort of natural equivalent to watching a calm film. Fish are constantly in motion and swim flashing in and out of light. So it's no wonder that many pioneers of animal film began by looking at aquariums. In A Fish Family, produced by the American Moody Institute of Science from 1957, the cichlids swim placidly about while a commentator explains that the mother and the father work as a team, dispensing the family chores together as we humans do. We need only take a leaf out of their book in order to lead a happy family life with mom, dad and the kids. Nature has shown us how to do it.

The perspective has somewhat shifted in Pavlov's famous dog lab in Saint Petersburg, later Leningrad. Conditioned Reflexes in Animals (Pavlov) from the 1920s makes it clear that, given the right methods, any animal can be trained to do all manner of things. This mechanism nevertheless quickly reaches its limits. You can't get cats to stop chasing mice.

Chen Sheinberg, master of the entomological art film, makes this clear. In Convulsion, he shows an upturned and therefore screaming beetle. The cries of the animal are the only sound in the film and are of course authentic. The beetle would never get back on its legs on its own. It would need a helping hand or a strong gust of wind. As soon as we observe an animal their difference to us comes into play. Matter-of-factness can help to cope with this difference without taming it. Zimmerleute des Waldes (Carpenters of the Wood), one of the first films by Heinz Sielmann, is one such document of matter-of-factness. Sielmann was the first animal filmmaker to show what goes on inside a woodpecker's hole as eggs are being brooded, as the babies hatch and grow up. The only German film maker to manage to become an animal in name as well as in nature, he was afterwards referred to in England as Mr. Woodpecker. As his film came out in 1954, even Sielmann could not afford to complete the break between human and animal. The ironic commentary to the film draws the woodpeckers again and again into the human world. Nevertheless, in terms of method Sielmann remains a predecessor to those film makers like Heinz Meynhardt with his Wildschwein ehrenhalber (Honorary Wild Boar) by assuming that animals can only be understood by treating them as animals, not as humans.