Übergordnete Werke und Veranstaltungen

Museum of Non Participation

Personen

Media

Marcel Schwierin

KAREN MIRZA & BRAD BUTLER, Museum of Non Participation

The Museum of Non Participation is a project of the other places. Karen Mirza and Brad Butler counter the current concept of the museum as a closed container for the conservation of established art with the original Greek notion of the museum as the vital ‘place of the muses’ – which premises an essentially imaginary calibre. The museum by today’s definition is a site of exclusionary practice: it is accessible as a platform to very few artists respectively artworks and – in global terms – to a very limited number of visitors. Contemporary art is excluded on two counts: neither museums (unlike the muses) nor the public are partial to it.

Karen Mirza and Brad Butler are from the UK, a country full of museums that are in turn full of de-contextualized cultural artefacts. They travel a great deal, as almost all grants for artists today are bound to a particular location – a point reflected also in the .move title. They thus found themselves once in Pakistan's capital, Karachi, a city with practically no museums, a city where contemporary art is barely present. In this post-colonial situation they developed the concept of another museum, a museum as an act of intervention, a museum as a locus of dialogue.

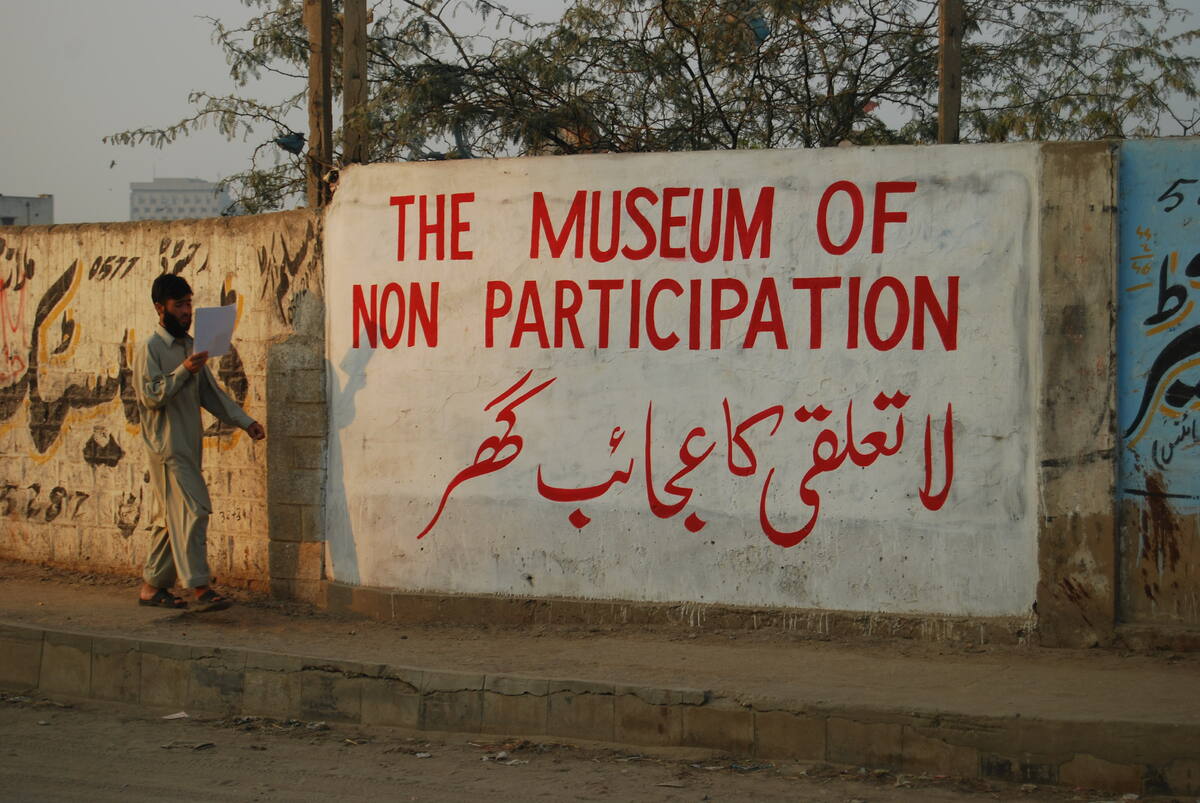

The Museum of Non Participation is bound neither to a place nor a medium; nor is it established, who is the artist and who the recipient. The classical path of the western ego – here the artistic genius and his work, there the public, between them the museum, as a mediating instance – is to be diverted by a more collective, more discursive form of participation. In consequence, workshops, public talks, city tours and readings were instigated in collaboration with local artists, authors and activists. Communicating by means of murals, which is common in Pakistan, was adopted in order to anchor the project in public space.

Therefore, when Brad Butler, Karen Mirza and activist Raymon Abdullah together execute a public mural in Karachi – in this case, the Museum of Non Participation – it exists as such, even if nothing more takes place at the site. The Museum of Non Participation is a museal assertion. The paradox of a title that actually describes the case of a normal museum in which neither artists nor the public participate is an ironic challenge, and points to the imaginary nature of the project. It really is a non-museum.

In The Exception and the Rule (Pakistan/UK 2009, 37 min.), a film shot in Karachi as part of the Museum of Non Participation project, the aforementioned challenges crop up again in a similar style, which references problematic aspects of the ethnographic documentary film. How might one make a film about a foreign culture and thereby get away from ones own inscribed images of that culture? Furthermore, is it possible to make such a film and thereby include the perspectives of those being filmed? And, finally, which film genre is able to deal with this kind of theoretical issue?

The result is an extremely idiosyncratic hybrid composed of various genres that do notpermeate one another but are presented consecutively, in such a manner as to be cited as methods. Genres such as the classic ethnographic film pop up along with the experimental genres first person documentary, conceptual film and the fake.

The Exception and the Rule opens with images of homeless people in London, shot in the style of a news broadcast. In the context of a film about Pakistan, this references the scenes of misery typical of news reports on the Third World, which allow one to forget all too easily that blatant poverty is equally at home in the rich West.

The title ‘film is only comfortable with otherness as long as it’s not really other’ draws a line between the folkloristic Other whose existence is reduced to a pretty picture and the real Other, Islamic fundamentalism for example, that aggressively and successfully represents a completely other world order, in which not only the maker and viewer of this film would have no place but the artistic medium film itself.

Documentary images of Pakistan are merged with newspaper clippings in long double exposures, which on the one hand references script as a defining form of cultural expression in Islam and, on the other, how the media represent and thereby simultaneously inscribe a culture.

The filmmakers asked musician Nigel Colasco to describe for the camera what he could see behind the camera. Thus the image – that one initially might presume is part of a typical street interview – becomes a refraction of the medial gaze in several respects. The viewer is told about what s/he cannot see, not through the eyes of the foreigner but through those of a native – who, contrary to the original conceptual guidelines, goes beyond a mere description of what he can see and begins to interpret it.

In another sequence, the result of a workshop, artist Adeela Suleman reperforms the conceptual film 30 Sound Situations (dir. Ryszard Wasko, Poland, 1975), by banging together two wooden sticks in public space. Wasko’s ironic medial refraction (which was to take a technically superfluous part of the film as the theme of his work) here becomes a radical intervention in society: Adeela Suleman exposes herself in public, her hair loose and uncovered.

Mirza and Butler not only cite Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène’s criticism of the doyen of ethnographic film, Jean Rouch – ‘you observe us like insects’ – but also the language of the classic documentary film with its black and white, seemingly authentic images: only then to break the latter with garish, artificial-looking colour stills depicting the same motifs.

The rapid succession of images of political demonstrations appear simple to read – one is familiar with images of the angry Islamic mob – until strange signs suddenly pop up among the crowd: ‘BE.INDIAN/BUY.INDIAN/GOODS.ONLY’. The enmity of the ‘good’ democracy India towards the ‘bad’ dictatorship Pakistan informs the medial perspective on the country.

A documentary-style sequence of beautiful and rare images of Karachi is – like the classical travelogue film – accompanied by a voiceover that in this case is not translated however. The viewer is thus left alone with his lack of knowledge of Urdu and the images.

If the Museum of Non Participation is a non-museum, The Exception and the Rule is a non-documentary film. One learns as little about a foreign culture via the media as one learns about the vital artistic moment (symbolized in myth by the muses) via a museum. The film entwines images of the Other in a complex interweave of medial references and formal refractions; it insists on the moment of non-communicable experience – and thus exacts from the viewer the direct, ‘uncomfortable’ encounter with the real Other.

Karen Mirza & Brad Butler define their contribution to .move as part of the Museum of Non Participation:

‘The residency in Halle culminates in the form of a site specific performance in the Intecta building, a former department store from the early 20th century. This performance looks at both the social history of the space and the performativity of the architecture. In Halle we have sought to research and interrogate place, history and the imaginary future. As part of our collective and discursive procedural approach we take different attitudes and positions towards agency, social understanding and political action. Our process of inviting participants into the research took the form of a non hierarchical workshop framed around the concept of “reclaiming the city”. This took as a starting point our recent film, The Exception and the Rule which has been shot in Karachi, Pakistan, this year.’