Übergordnete Werke und Veranstaltungen

Horizons

Personen

Media

The Meta-cognition of Space

The Berlin-based artist Egemen Demirci investigates the notion of space in relation to diverse aspects of artistic research, exhibition making, circulation of art production as well as critical thinking. He works with different materials, contextual references, and strategies of approach focusing on where we live and how we change where we live. He developed a text-based large-scale installation employing neon light for the Werkleitz Festival, in continuity to his research-based work, which he has been sharing with me for many years. In the following interview we discuss research and preparation processes, production details, and decisions about the installation.

Misal Adnan Yıldız: Can you start with the simple idea of Horizons? How did you come up with the project?

Egemen Demirci: Horizons came out as a response to a series of political events around the globe in the last couple of years and the situation we are facing now, the common problems surfacing in the aftermath of these events. To put it simply, I feel the attempts to change things fundamentally lack two crucial elements; organization and an alternative to the existing situation. What interests me here is the perception and construction of these alternatives, which is fundamentally a problem of time and space. In this sense, I am drawn to the notion of “the unknown”. How can we think of something about whose existence we don’t know anything? How can we imagine something beyond the grasp of our experience and intellect? How can we include things that we cannot relate to in our daily lives? There is also a question of why would we do any of these things. But I also believe they are strongly political questions. Following this inquiry I started looking at ancient philosophers like Anaximander (ca. 610/09 – 547/46 BCE), who was one of the first – at least in the Western world – to try to come up with a systematic analysis of how the universe is constructed. This was pretty much the starting point of the project.

MAY: What can you tell us about your material research?

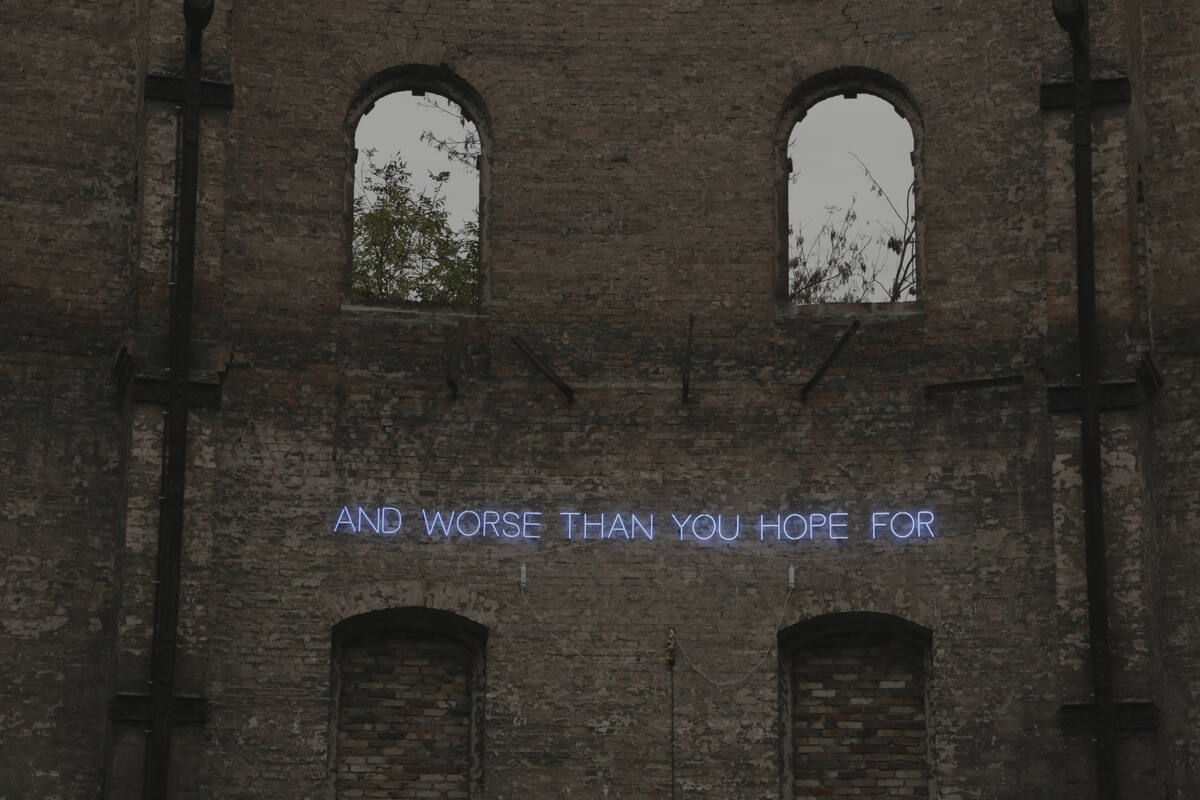

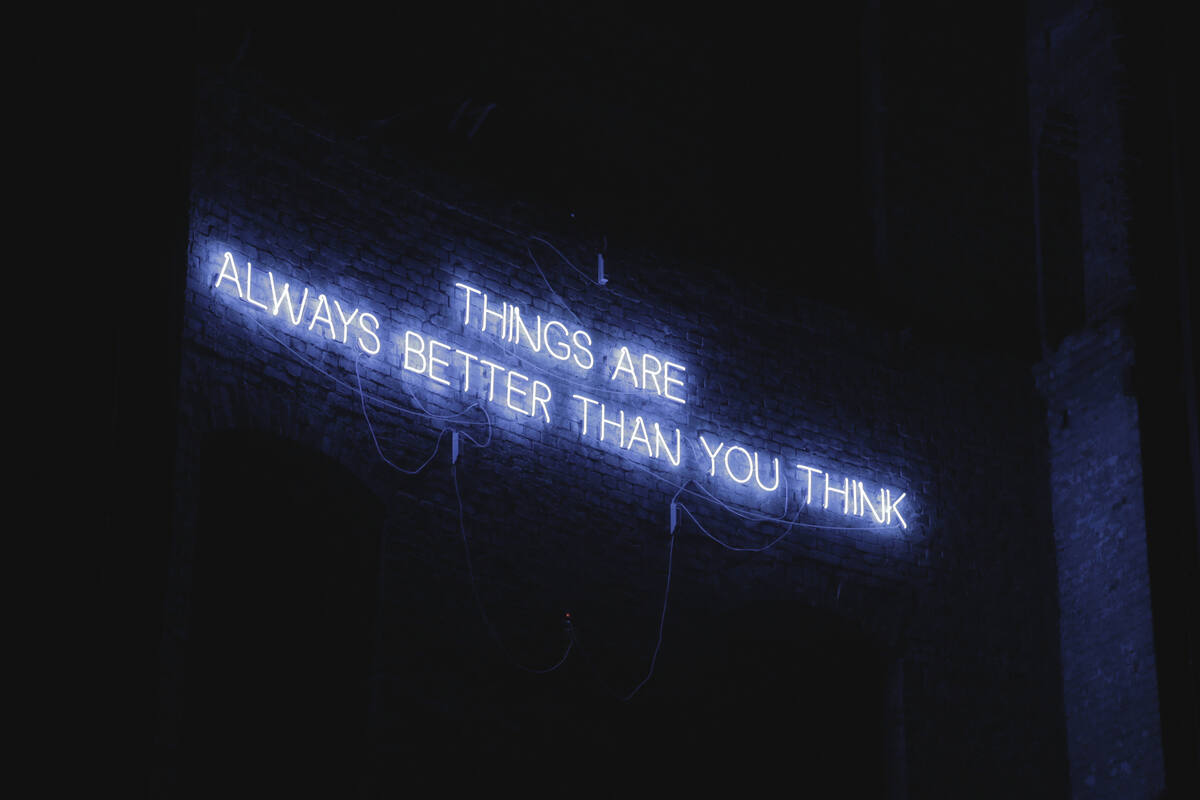

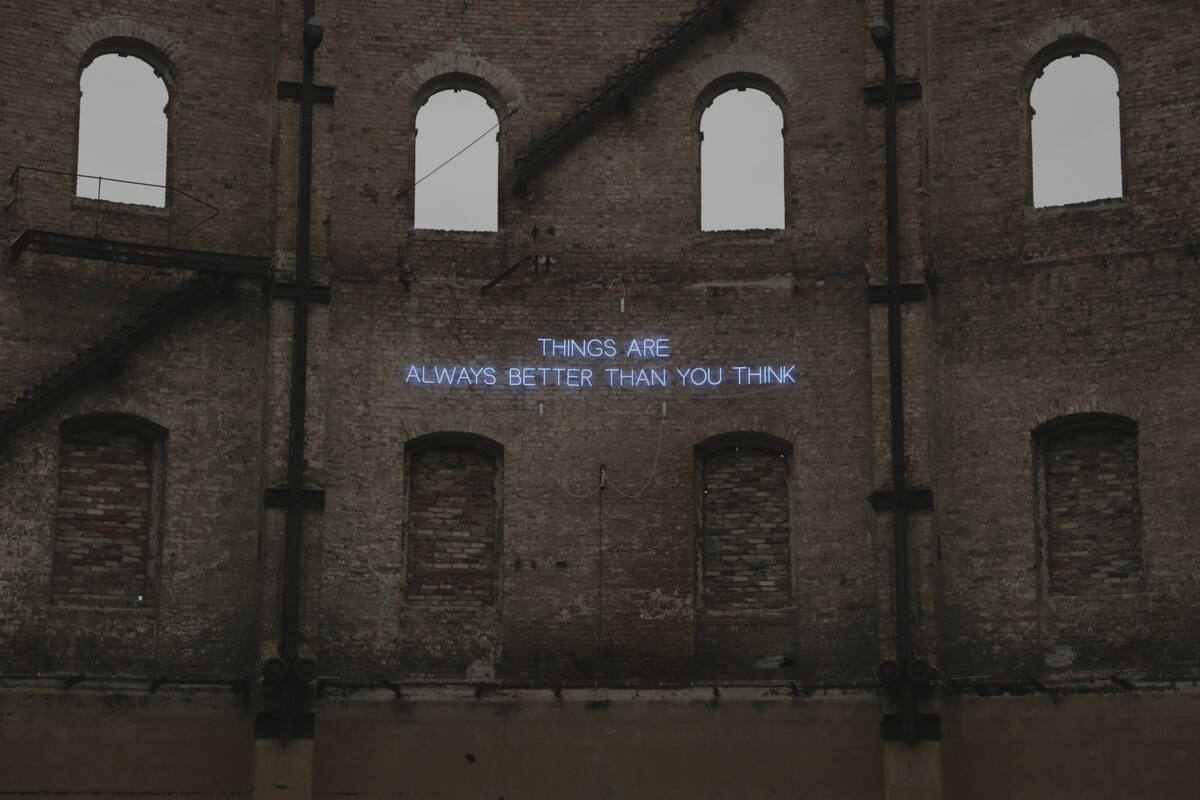

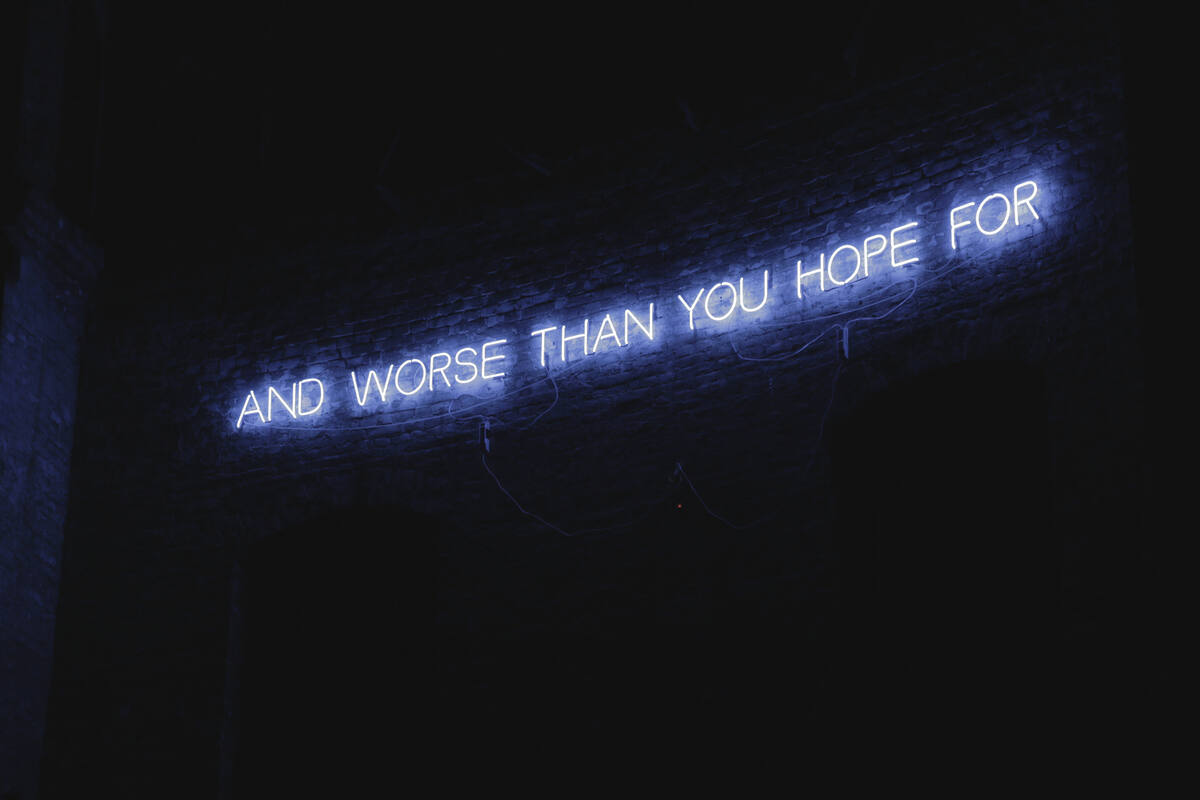

ED: Both the work in the gasometer and in the Technikhalle is about perspectives. From the start, I was thinking about what would be the best material to produce the work in the gasometer, and at first there were several possible locations, which would determine the material. Also, there is a typography I have been working on for about a year, which would be impossible to make with neon letters. But in the end, when it was decided we would be using the gasometer, I wanted to use a material that would not only be seen in the space but fill up the space and even at certain times of the day pour out of the space. This has also to do with the notion of reality I wanted to tackle with the work. So using neon letters was then the right choice. Nevertheless, for both of the works I believe light turns out to be the main material.

MAY: What were the main steps during your production process?

ED: The interesting thing for me using transparent plexiglass and neon light was the choice of colours for both materials from a limited and basic selection. This is the point when industrial and commercial production actually sets limits to the potential transformations of artistic production. Up to a certain point I like staying within these limits since it makes the work a reproducible original, bypassing the critique – and not a unique work of art which can never be produced again, an unpopular approach today. I can add to this historical remark that, although there is a clear reference to Suprematism in the drawings, the starting point here for me is not the disqualification of the object but rather the observation of its transition from a material entity to data. So instead of seeking a non-objective world it is about the de-materialization of the object and how we use the resulting information to construct a meaningful setting.

MAY: What about the structure of the sentence: things are always better than you think and worse than you hope for? On the one side you seem to be giving hope but on the other side you want us to keep our feet on the ground. You are in dialogue with the audience. Can we call this cognitive realism?

ED: Cognitive for me covers a very wide area. I do not believe I have the time to discuss the notion of reality, which itself is a very tough and deep subject. In the sentence, as you said, there are two perspectives, but reality is singular. This shows on the one side a dialectic which repeats itself in our lives and on the other side differences in perception and interpretation facing a continuous and steady reality. What is fundamentally and crucially important for me is to challenge the notion of subjectivity, the anti-Copernican world view that puts the subject at the center of the universe.

MAY: What audience responses to your work have you been able to observe?

ED: Of course people want to look at things and develop relations amongst them in order to understand what is exhibited. For me it is problematic when these relations are formed only retrospectively, either through the artist or through the research, topic, process etc. In both of these works, I was interested in somewhat more structural relations, for example the jump from the unique acoustics of the gasometer, which compels people almost immediately to make sounds, to a linguistic proposition. Also in the drawings / wall sculptures there is a repeating closed circuit formed with the geometric representations of objects and their deconstructed forms. This structural turn allows me to step outside of historicity and the retrospective reference system.

Misal Adnan Yıldız