Übergordnete Werke und Veranstaltungen

Performance

Dancing On My Life

Personen

Media

In the Swamps of Utopias

“What we Do. What we do is never understood, but only praised and blamed.”

…spoke or rather wrote Nietzsche in 1982 as the 264th aphorism from book 3 of his Gay Science.

With these words, the philologist Nietzsche laid down the stumbling stone for that political contention over the artistic act that has continued to the present day, while providing at the same time salvation from it. The pronouncement is unmistakably a reference to the utopian condition that should be permanently held in view but never can be made real. Utopia, often the aim of art, can only exist in the observer’s imagination, in a state reminiscent of Jean Genet's longing when he saw the unicorn emerging in a mythic landscape.1

Film and video art stand partly in the tradition that appropriates technologies of the state in order to counter its empty or illusionary promises. They are the very arts that are most seldom understood in this way. When these time-based media are shown together with traditional means of expression – painting, sculpture – artists and curators risk being criticised by the public as dilettantes.

We nevertheless constantly try to get closer to the state of utopia, to the free space of unbounded thought, decoding it with the diverse languages of art and its vocabulary. If we believe in Nietzsche's aphoristic promise that the fog of critique becomes denser the closer we come to utopia, then we need to go our way, until the crack of doom called failure brings forth not the longed for utopia but rather the gloom of dystopia. A crack simply.

“Without having seen the pieces, the title ‘Utopien vermeiden’ immediately catches my eye. If you take this seriously and understand it as a point of view being put forward then it seems to me a fatal sign. As a comment on society it is nothing more than the self satisfaction of a scene that already knows its codes (networks, contacts) and wants nothing more than its own aggrandisement. But today especially it is all the more important to start developing utopias, instead of utterly rejecting the idea that we need them. It seems to me that we do need them. Or am I mistaken?”2

As such, utopia is lying in a swamp, a place into which we can project dreams and fears, a place we can imagine but never really enter without losing our being. Every man for himself!

In order to be able to make art, utopia, as the conceivers of the Werkleitz Anniversary Festival have it, must be avoided. Nevertheless, art finds its protected spaces in such nebulous places, swamp-like, the swamps of utopias, at home in the landscapes of complex experiences and historical contexts which the art that merely exhibits can never uncover. The swamp is a dilemma, a predicament, whose avoidance is lodged paradoxically within the act of artistic examination itself.

“This ‘festival’ is once again a sheer waste of money by a pseudo-intellectual clique unable to appreciate the real value of work. At a remove from reality, they freeload at the cost of the normal, working, taxpaying population, as so often happens in Halle. The money that is wasted here should be put into the real cultural centres, like nt or the opera. If this kind of nonsense is being supported it can't be as dire as all that with financing for culture!”3

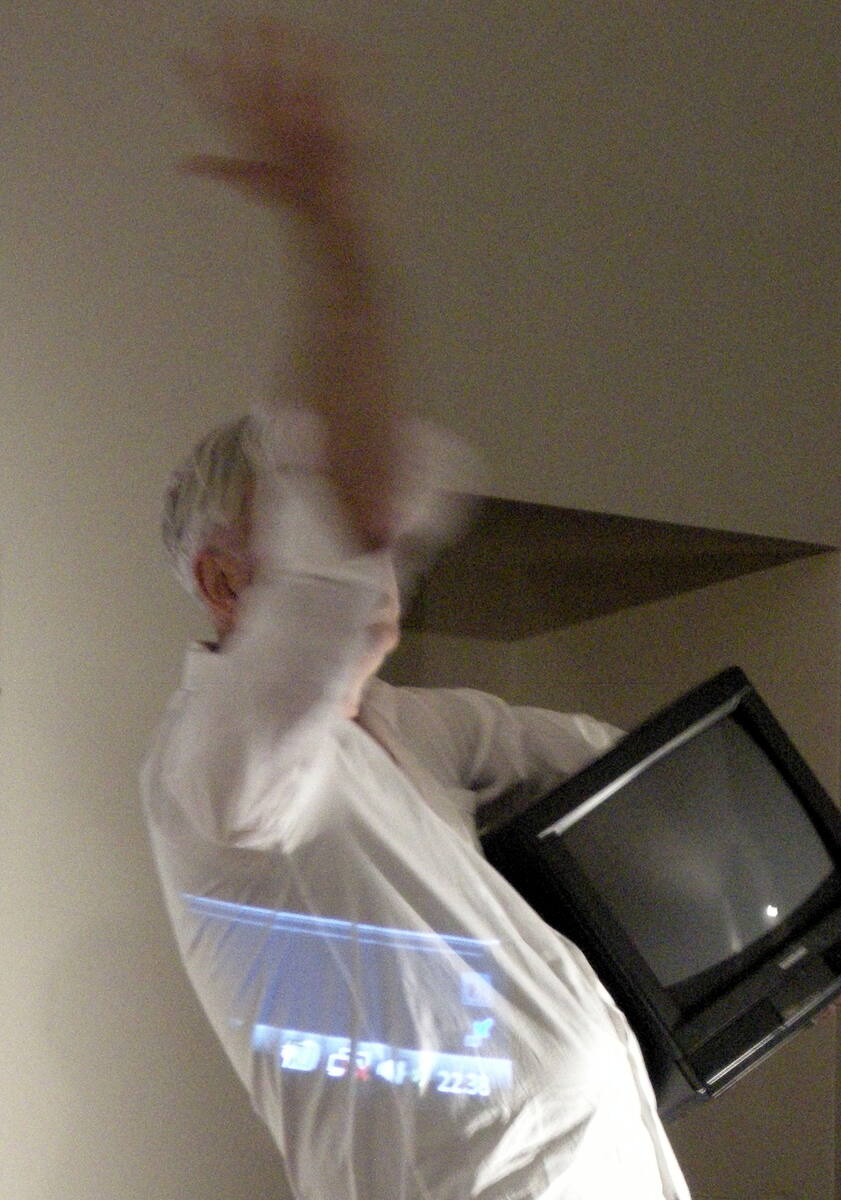

At a turn of the century with the most flagrant destruction caused by new industrial technologies, there can be no locus of cultural production more symptomatic of the historical fields of power struggle between the European Orient and Occident than the Serbian province Vojvodina. In his performance, Dancing On My Life, the artist Bálint Szombathy depicts his own subversive, semiotic, artistic career. This career extends from Novi Sad, the capital of Vojvodina, to the Hungarian capital Budapest. In order to reflect on this landscape (one of the most multi-ethnic regions in Europe, binding together the cultures of the most diverse nationalities) in the context of 20th century German history, Szombathy selects the relics of his own, deeply rooted memory: electronic appliances from classic 1950s radios to gramophones and cassette players, televisions, computers, mobile telephones. Everyday tools for listening to music. Aware of our connectedness as European citizens enjoying equal rights of participation in his Life-Performance, he essays a collective cultural and political excursion.

“My commentary was purely about the content of the conspicuous title ‘Utopien vermeiden’. I was not trying to ally myself to the commentary of ‘Steuerzahler’. On the contrary, I view the commentary of ‘Steuerzahler’ as playing into the hands of the opponents of cultural spending. Nothing could be further from my intentions.”4

Szombathy leads a course and discourse through a history that is not only his but also ours. He draws conclusions from the political unrest of this violent and at the same time sobering century, from the agonies of war, persecution and collapse.

“Someone selling an atomic catastrophe as ‘art’ (including bang, sirens etc. - as happened at the Werkleitz Festival) on the day a German armed forces soldier from Halle is buried, this person has lost all social competence and won't be influenced by the commentary of Steuerzahler. Keep on celebrating yourself!”5

Szombathy’s performance is based on the work of the Austro-Hungarian pioneer dancer and choreographer Rudolf Lábán (1879–1958), focussing on his approach to choreography as a free form of expression. Lábán’s work can be regarded in the context of the convulsions that shook Europe in the first half of the 20thcentury as a striving for utopia with an unshakable belief in the leading role of art. Lábán was living in Berlin teaching dance in the 1930s as the Nazis consolidated power. He was neither German nor a party member. He was able to elide the unequivocal ideological shift in the arts by playing the regime's tune only as long as he could attain his own objectives in dance. Lábán’s search for ultimate freedom manifested in the deeply felt need to free himself from traditional forms of expression and from social norms.

In the face of the dance the artist Szombathy staged as an agonised homage to the origins of Lábán the onlooker stands like Jean Genet – uncertain, hesitant. The dance introduces us to the foundations of Labanotation, the dance notation system for which Lábán is most well known today, especially in the German culture scene. This code is an historical cultural language that degrades anyone not passionately involved to the status of voyeur. At the same time it functions soothingly like balsam on an open wound. “The semantic codes of the curators resist approach by the uninitiated despite sincere attempts at mediation.”6

“to mathiasschulze: I do not want cultural spending to be cut, but rather real culture to be supported! If you stick peacock's feathers into a swine's arse, you've still got a swine!!! In Halle, dubious projects are often covered up with the cloak of art and given financial support. In view of tight budgets this must stop!!!!”7

The artist Szombathy now turns on all the machines. Acoustic distortions accumulate while a video shows the artist in front of an orchestra, dancing to popular folk music. At the same time he begins a live “dance” in which he treads on his instruments. Their cracking sounds decay slowly, leaving only the tones of the orchestra playing.

“To Steuerzahler: As I was saying, I have not seen any of the things mentioned. But the fact remains that behind the discussion not only the question lurks of what is real culture but perhaps also the much more interesting question of who actually belongs to the so-called free scene (not only in Halle, but in all of Germany). Students? Interns? Young people clamped between computers hearing the divide between rich and poor slamming shut? These people are clearly going to be willing and able to make different art than we are familiar with from the opera and the state theatre. It is definitely too simple to pigeon-hole them by saying they do pseudo-intellectual things that are not art. In Leipzig the new theatre directorship under Enrico Lübbe just began, accompanied by the same discussions. Maybe it would help to get to know the living environment of the free creative artists. The environment namely conditions the understanding of culture.”8

So the artist dances through his life, a life inseparably bound up with our common cultural century. He is not distracted by the threatening crack-up, banking on Lábán’s destructive digressions from norms – as personal distortion of utopian ideals. In the process he annihilates some of his most sacred objects of reverence.

“*If one didn't take Werkleitz as seriously as they take themselves one could even like some of the things they do. Artists sometimes think they're the avant-garde of society, which in my eyes they are not. True, it sometimes seems they're just a community for the attainment of subsidies who meets in a closed circle to pat each other on the back. Yet at the same time they're a little splash of colour in our lives.”8

In the swamps of utopias – keep it up!

Stephen Kovats

1 Cf. Un Captif Amoureux, Paris 1986 (Prisoner of Love). Genet’s posthumously published reaction to his experiences in Palestine at a time of crisis is a treatise on revolt, a meditation full of mythic visions whose seductive and dangerous character make what Genet grasps as reality complicated to prove.

2 'mathiasschulze', comment, Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 12.10.2013, 14:45 h. http://bit.ly/1opvdZG [29.04.2014]

3 'Steuerzahler’, comment,Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 12.10.2013, 16:26 h.

4 'mathiasschulze', comment,Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 12.10.2013, 18:47 h.

5 'Bernd_WPunkt', comment,Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 12.10.2013, 19:43 h.

6 Günter Kowa, Werkleitz-Festival in Halle: Glaubt keinem Versprechen. Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, 12.10.2013.

7 'Steuerzahler', comment,Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 12.10.2013, 21:03 h.

8 'Kritiker', comment,Mitteldeutsche Zeitung online, 13.10.2013,, 09:18 h.

Normal 0 21 false false false DE X-NONE X-NONE / Style Definitions / table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Normale Tabelle"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt; mso-para-margin-top:0cm; mso-para-margin-right:0cm; mso-para-margin-bottom:10.0pt; mso-para-margin-left:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Cambria","serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}