Übergordnete Werke und Veranstaltungen

Seh' ich was, was Du nicht siehst?

Personen

Media

Somewhere, a tenderness:

On Fassbinder's "Whity"

”Somewhere, there is a tenderness that has no room in the minds of these people.” (1)

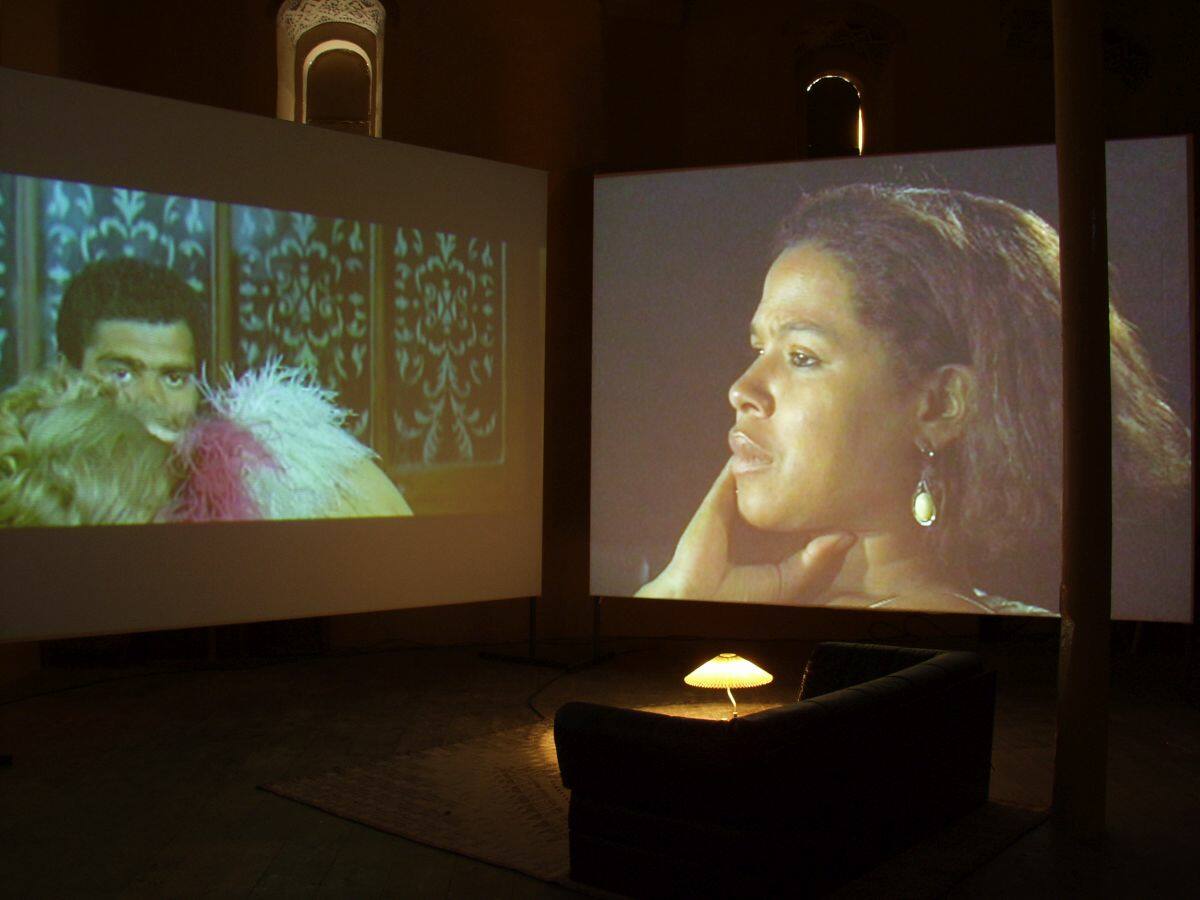

The first image in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s cinemascope Western melodrama Whity (1970) is a still of the title character’s black body in a white suit (Günter Kaufmann), lying face down in the mud, clutching a red rose. Peer Raben’s opening song, “I Kill Him”– sung by Kaufmann himself – accompanies the image as well as the credits, which are projected onto Whity’s body. The image is repeated later in the film at the end of the scene in which Whity, a mulatto slave, is beaten up by a bunch of rowdy cowboys and thrown out of the small town saloon. Whity had come to the saloon to see his white lover Hanna (Hanna Schygulla), the saloon singer and town whore. Upon his arrival, Hanna sings him a song, walks slowly over to him, presents him with a red rose, sits on his lap and, at the song’s end, kisses him on the lips. Her attention to Whity irritates the white townspeople in the saloon, in particular one gruff guy at the bar played by Fassbinder who announces, “That’s enough!” and challenges the others, “Are you all cowards?” Led by this cowboy, the other men proceed to beat up Whity, who offers no resistance whatsoever, and throw him out the door. The scene ends with the above mentioned close-up of Whity’s beaten up black body, face down in the mud, one hand cradling Hanna’s red rose.

I Kill Him

Fassbinder’s protagonists often get beaten up or beaten down. Indeed, some of the most memorable images from his films are those of bodies beaten up, thrown out of apartments, exhausted from drink and drugs, and left to die before our very eyes. To mention just a few of my favorites: there’s the beginning of "In einem Jahr mit dreizehn Monden" in which the transsexual Elvira (Volker Spengler) gets beaten up while cruising for sex in a Frankfurt park and the end of the same film with Elvira collapsed dead on her bed; the end of Faustrecht der Freiheit in which the homosexual Franz Biberkopf or Fox (Fassbinder) is lying dead in a subway station, his corpse robbed by a couple of young kids; or the end of "Der Händler der vier Jahreszeiten" in which the fruit peddler Hans (Hans Hirschmüller) drinks himself to death in front of his family and friends and collapses onto the table in the bar. The stories that accompany these images typically detail the various betrayals, double-crossings or sleazy economic deals that drove someone to suicide or led them to getting thrown out, beaten up, or killed. What’s most striking perhaps in Fassbinder’s tales of abuse and social injustice is that his protagonists – who are often members of oppressed groups in society, women, blacks, foreigners, homosexuals, working class people – display no self-pity. They not only complain very little about the social injustices that are heaped upon them; rather, some of them really seem to enjoy these abuses. Take the slave Whity, for instance, who eagerly offers his black body to be whipped by his white master as a substitute for that of the master’s white son. Whity receives the blows of the whip with an expression that resembles pleasure as much as pain. As Thomas Elsaesser has noted, one often speaks of Fassbinder’s representation of social outcasts in terms of victimhood. If we continue to do so, he suggests, then we need to understand victimhood in Fassbinder not as a problem state from which the characters attempt to escape, but rather as already a “solution”. As he puts it, victimhood in Fassbinder is “a way of repositioning the dialectic of oppressor/ oppressed, refusing the complicity of the power struggles over sexual and class identity. Some of Fassbinder’s protagonists seek salvation and integrity not outside the barriers of sex and class, but by living exploitation from within ...What appears to be defeatism or mere self-abandonment, in fact founds another truth of selfhood and thus corresponds to a different – differently gendered and in the present society unliveable – morality. Death, unbearably pointless as it may seem, is not a defeat for them, but the memorial to a victory as yet deferred.” (2)

By refusing his protagonists an escape route outside the barriers of sex, class and race, Fassbinder forces them to explore the possibilities of resistance from within. We could perhaps extend Elsaesser’s observations and suggest that part of the radicality of Fassbinder’s politics of marginality stems from, what we might call, his critique of the outside. By outside, I’m thinking of the utopian notion that there could be a space removed from the messiness of race, class, gender, and sexual inequities from which one could safely critique the powers that be. Fassbinder’s critique of the outside may be one reason why his representations of minorities won’t go down so easily with liberals. As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri put it, “the end of the outside is the end of liberal politics.” (3) Liberal politics, they argue, is dependent on the clear (modernist) distinction between inside/outside, with the outside distinguished as the proper place of politics, the place “where we act in the presence of others.” But faced with the transformations of global capital, the massive spread of communication and information networks, the place outside is no longer so easily differentiated from that of the inside. For Hardt and Negri, “the modern dialectic of inside and outside has been replaced by a play of degrees and intensities, of hybridity and artificiality” (187-8).

Anyone need an intrigue?

Whity is set in a desolate small town somewhere in the American West in 1878. It tells the story of the Nicolson family: the strong-armed patriarch Ben Nicolson; his spoiled, perverse second wife, Katherine; his two sons from a previous marriage, the homosexual, Frank, and the mentally ill, Davie; his slave, Whity, who is also his bastard son, and Whity’s black mother (4). Whity is both the family’s object of desire and object of contempt. Each family member attempts to seduce him and solicit his help in killing Ben Nicolson, so that they alone could inherit the Nicolson estate. Though Whity submits readily and without resistance to their taunts and abuses, he reacts silently to their erotic and violent solicitations. At night, he goes to meet Hanna either in the saloon or in her bedroom, which he dutifully enters from the window after waiting patiently for her clients to leave. Hanna urges him to leave the town and this horrible family who abuse him. But Whity insists on staying. In the end, he murders each one of them and flees. In the final scene, he and Hanna are seen in the desert where, without enough water, they will most certainly die of thirst.

Whity was the first film Fassbinder made outside of Germany and as such it marked a significant departure from his earlier work. Thanks to the money the anti-theater group received for the Bundesfilmpreis for their 1969 film Götter der Pest, they were able to afford a budget that was more than three times the amount of any previous film. (5) According to Kurt Raab, actor Ulli Lommel, who had a budding interest in producing, suggested to Fassbinder the idea of filming in Spain (6). Fassbinder immediately agreed to it and quickly conceived the story of the mulatto servant of a white rancher family in part in order to feature Günther Kaufmann, his then current love interest. Shooting away in Spain also played in perfectly with Fassbinder’s plan of getting Kaufmann away from his wife and kids in Bavaria. Whity was shot in and around Almeria, the same region in Andalucia where many Italian spaghetti westerns were filmed. Similar to those films, Whity borrows from Hollywood, most notably from Raoul Walsh’s Band of Angels and Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco. Such was the case with Fassbinder’s previous films as well, which appropriated Hollywood genre motifs, mainly from gangster films, to the contemporary urban settings in Munich. Those films displayed a matter-of-fact realism that was lent a degree of criticality through the artificiality of the anti-theater presentational style. Whity, however, was the first Fassbinder film to cloak itself fully in the look and feel of a grand-style Hollyood period piece. As such, it was his first film to have a concerted costume and production design. (7)

At its premiere at the Berlin Film Festival in 1971, Whity caught critics and audiences off-guard. The film was a total flop and never appeared in theaters or on television. It is still widely regarded as Fassbinder’s least successful film. (8) Critics at the time tended to attribute the film’s failure to its foreignness -its Western setting, costumes, set design and beautiful cinemascope technicolor. In contrast to Fassbinder’s earlier films which were read as speaking directly about issues of relevance to contemporary Germans, Whity displayed, according to critic Alf - Brustellin, “a, by this time, completely secondary experience.” (9) This denial of Whity’s topical relevance – though hard to believe from a contemporary perspective – permeates most of the literature on Fassbinder’s films, with Anna Kuhn expressing a characteristic sentiment in her description of Whity as “a self-contained melodrama devoid of criticism of postwar German society.” (10)

The lack of regard for the film in critical scholarship about Fassbinder’s work is countered by the film’s almost singular importance for Fassbinder and his co-workers. Kurt Raab for instance regards the film as “ something like a key film for me, not in terms of form and content, but because I became aware of certain forms of behavior with Fassbinder that until then had remained concealed to me.” (11) For Fassbinder as well, the film was central, not because of its big budget or its big-scale Hollywood genre look, but because the production offered him a perspective on the personal relations within the anti-theater collective. As he noted in an interview,

“That it was a western and a film with a big budget is not what is so important to me. Rather the fact that for the first time the group was able to be considered from the outside....It became clear that many of the relationships in which one believed no longer existed or existed differently than one thought. In Munich everything was very quick. It was crazy, ten films in a year. One was constantly busy. Outside, in Spain there was a kind of crystallization, of some relationships that revealed themselves to be non-existent, of others that were profoundly transformed... Maybe this is the most important thing about this film.” (12)

Being outside of the country, outside of their typical working situation for the first time, Fassbinder and his crew developed a perspective on the dynamics of the group. For Fassbinder, this experience and perspective from outside, was decisive. It led him not only to restructure the working and living situation of the anti-theater collective, but also to call into question “the dream of the collective” altogether. (13) This dream ZUGEWINNGEMEINSCHAFT of the collective was a dream for a kind of outside – within a kind of utopian space where through one’s life and work one could critique the existing power strucutre. In this sense considering the group from the outside offered Fassbinder a perspective on the outside itself.

Goodbye, my love, goodbye

“ct: It very rarely happens that your characters actually rebel against the conditions they live in. Though it does happen in Whity, where the slave kills his master and escapes.

rwf: Yet in actual fact, the entire film is pitted against the black man, because he always hesitates and fails to defend himself against injustice. In the end he does shoot the people who oppressed him, but then he goes off into the desert and dies, having come to realize certain things without being able to act. He goes into the desert because he doesn’t dare face the inevitable consequences. I find it OK that he kills his oppressors, but it is not OK that he then goes into the desert. For by doing that he accepts the superiority of the others. Had he truly believed in his action, he would have allied himself with other oppressed individuals, and they would have acted together. The singlehanded act at the end of the movie is not a solution. Thus, in the last instance the film even turns against Blacks.” (14)

In contrast to its opening image of Whity’s beaten up/beaten down body, the film closes with an image of Whity’s upright body, dancing with Hanna in the desert. Of course, they are dancing with full knowledge of their impending death. That they know they are going to die has already been made clear by the one line of dialogue spoken in the scene, Hanna’s matter of fact response to Whity’s actions of drinking and pouring over his body the remains of their water supply: “It is clear to you that we will now die of thirst.” Whity doesn’t respond to Hanna. They both then frolic in the sand together only to eventually get back up again and start dancing, as if prompted by the sound of the closing song heard on the soundtrack. The song further emphasizes the impossibility of their love, of their quest for a future together outside. “It doesn’t go together. Your way of life and mine... Goodbye, my love, goodbye.”

These complex and beautiful final images of Whity display a kind of tenderness that surfaced only occassionally at other moments in the film— mainly in connection with Hanna and Whity or with Whity and Davie. By differentiating between Whity’s prone body at the start of the film and his upright body at the film’s end, I by no means intend to suggest that Whity somehow narrates the story of a successful uprising. Nor do I consider the desert a somewhere for a tenderness that has no room in the minds of these people. Rather, I take the complexity of information in the final images – the upright bodies; the expression of tenderness; the expression of their inescapable incompatibility; and the fact of their impending death – as Fassbinder’s way of communicating the impossibility of a simple outside to the forces of social and racial oppression depicted in the film. As he puts it, “You have to show people how they could put up resistance without ending up in the desert”. (15)

Marc Siegel is a Doctoral Candidate in Film Studies at The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

--

1 Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Whity, in Rainer Werner Fassbinder Ed. Laurence Kardish with Juliane Lorenz (New York: MOMA, 1997), 91.

2 Thomas Elsaesser, Fassbinder’s Germany: History, Identity, Subject (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1996) 250.

3 Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2000), 189.

4 Perhaps I should say “blackened mother” since the actress appears to be in black face. Though the sons faces are whitened, those of Whity and the other characters are not noticeably altered. The film thus presents skin color in somewhat of a range of shades and tones. Could this be understood as yet another way in which Fassbinder refuses to give audiences a black and white story, so to speak, and instead presents racial difference as a play of degrees and intensities?

5 The anti-theater is the name of the artistic collective with which Fassbinder lived and worked since 1968. The group continued producing theater and then film under that name until their break-up/reorganization in 1971.

6 See Raab’s wonderfully gossipy account of Whity in his book, Kurt Raab and Karsten Peters. Die Sehnsucht des Rainer Werner Fassbinder. (München: Bertelsmann, 1982), 150-6.

7 Interestingly, Kurt Raab, Production and Costume Designer for Whity, won a Bundesfilmpreis for his efforts.

8 It is, however, the first Fassbinder film to have appeared on DVD in the United States.

9 Qtd. In Wilhelm Roth, Annotated Filmography, Fassbinder (New York: Tanam Press, 1981), 125.

10 Anna Kuhn, Rainer Werner Fassbinder: The Alienated Vision, in New German Filmmakers Ed. Klaus Phillips (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1984), 87-8. Thomas Elsaesser has initiated a shift in interpretations of Whity, suggesting links with Fassbinder’s ongoing concerns and interestingly thematic connection to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Teorema, made one year earlier, and certainly considered relevant to the concerns of the day. See Elsaesser, 273.

11 Raab and Peters, 150. Actor and Regie-Assitant Harry Baer’s biography on Fassbinder, devotes a whole chapter to der Film, der nie ins Kino kam. Harry Baer, Schlafen kann ich wenn ich tot bin: Das atemlose Leben des Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Köln: Kiepenhauer & Witsch, 1982).

12 Wolfgang Limmer, “Entretien avec Fassbinder”, Masques: revue des homosexualites No. 15 (1982), 46.

13 Christian Braad Thomsen, “Conversations with Rainer Werner Fassbinder,” in Rainer Werner Fassbinder ed. Kardish, 88.

14 Braad Thomsen, 87.

15 Qtd. in “Filmography” in Rainer Werner Fassbinder ed. Kardish, 53.